Regional Profile

Explore Burgundy

Gevrey Chambertin, Nuits St Georges, Meursault. Reading these words either fills you with fear or excitement depending on how much you know about wines from Burgundy. The region is without a doubt one of the most inscrutable and difficult to understand in the wine world.

True Burghounds spend their life understanding the minutiae of vineyards and winemakers. However, it only takes an understanding of a few things before the average wine lover can begin to understand Burgundy wine.

History of Burgundy Wine

No article on Burgundy would be complete without a discussion of the history of the region. Why is this important? Well, because sometime around 1000 CE vineyards began being tended by monastic orders.

The reason this is important is because monks could read, write and keep records. Years and years of record-keeping made them realize that some plots of land produced consistently better wine than others. This would provide the basis for naming and more importantly ranking vineyards.

It also helped to foster the notion of terroir in French wines, for what if not a “sense of place” could account for the fact that wines grown in one vineyard were better than another if not some mystical concept such as terroir?

Over the years, the nobility began to acquire vineyards, and the prestige and quality of Burgundy wines improved under the House of Valois. One king, Philip the Bold, went so far as to outlaw the widely planted Gamay grape, believing the wine was “unfit for human consumption”. This led to the rise of Pinot Noir, the red grape that is most widely planted in Burgundy wine regions.

After the French revolution in 1789, the remaining church vineyard lands were confiscated and sold off, but the most important and long-lasting aspect of the revolution on Burgundy was the Napoleonic Code, which required all lands to be equally divided among all children. This meant that vineyards were continuously subdivided generation after generation so that today holdings are sometimes as small as a row or two of vines.

The development of a corporation can protect vineyard holdings, since only the shares are divided and passed down, but Burgundians are famously independent, and this business structure did not take off here the way it did in other parts of France. And this is the reason Burgundy holdings are generally so small. Many producers make just a few thousand cases a year.

Wine Appellations of Burgundy

The detailed records kept by the monks in the Middle Ages helped to generate an awareness of the quality differences of different vineyards, or climats as they are called. When Bordeaux chateaux were classified for the 1855 World’s Fair in Paris, a similar classification was made in Burgundy. The big difference between Bordeaux and Burgundy, though, was that in Bordeaux the chateaux themselves were classified.

A chateau could be classified as Premier cru classé (or First Growth), which is the highest ranking in Medoc, for example. And if they decide to buy more land they could produce more Premier cru classé wine. However, in Burgundy, it was the land that was classified. Only so much wine can be produced from a Grand Cru vineyard.

Burgundy Wine: Quality Pyramid

Burgundy wine has been classified into four basic tiers. The lowest tier was regional wine, which was the most widely produced and least geographically specific.

The next step up was Village wine, which had to be grown within the confines of one of the named villages.

Next up was Premier cru wine, which had to be grown in one of the many quality vineyards. The top of the classification was Grand Cru wine, which had to be grown in the most prestigious vineyards.

Eventually, this classification was used when the Appellation di Origin Controllée system was established in 1936. Some changes are made over the years, but generally, the system has remained stable. Where this can become fascinating is there are many different villages, and some are ranked more highly than others.

Each village has many vineyards at either the village or Premier cru level, some of which you will see on a label. And these vineyards are ranked differently, even if they are within the same classification. For example, a Premier Cru wine from Givry will never be as highly regarded as a village level wine in Vosne-Romanée.

What this means is that the classification system is only a general guide to quality in Burgundy. Along with the classification system, a little knowledge of specific villages can be very helpful in understanding wines from the region.

Main Wine Regions of Burgundy

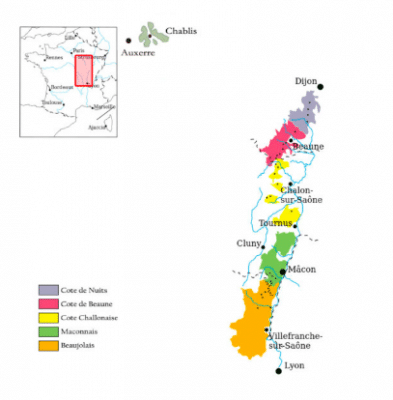

Burgundy is located in the centre of France and spans from Auxerre in the north to Lyon in the South, a distance of some 300 kms. However, it is divided into five regions that have very different styles of wine.

Côte d’Or

The Côte d’Or, or golden slope, is the heart of Burgundy. It stretches for 60 kms along a limestone escarpment South-West of Dijon. This region is where the most famous wines from Burgundy come from, almost all produced from Pinot Noir or Chardonnay. It is actually two different sub-regions: the Côte de Nuits and the Côte de Beaune.

Côte de Nuits

The Côte de Nuits is the northern half, where Pinot Noir is dominant. More than 90% of wines are made from Pinot Noir and this sub-region contains some of the most famous villages as well as the most famous (and expensive) red Grand crus.

The most important villages here are, from North to South, Gevrey-Chambertin, Morey-Saint-Denis, Vougeot, Flagy-Echézeaux, Vosne Romanée and Nuits-Saint-Georges.

Villages were allowed to append the name of their most famous grand cru to their name, so Gevrey appended Chambertin, Morey appended Saint-Denis, Chambolle appended Musigny and Flagy appended Echezeaux. In typical Burgundy fashion, Nuit Saint Georges is not Nuits appended by its grand cru, but rather its most famous Premier Cru, Les Saint Georges.

These villages mentioned above are certainly the most famous villages in Burgundy and they can command among the highest prices. Village level wines typically run from $50 to $100, 1er cru from $75 to $300 and Grand Cru usually $200 and over. However, winemaking is very good in these villages and wines are usually examples of Pinot Noir purity, delivering charm, style, complexity and finesse, and usually good aging potential if not requirement.

Value wines from the Côte de Nuits, if there is such a thing, are usually found in the appellations of Marsannay and Fixin, which can approach the style and weight of their more famous counterparts, if not the elegance and complexity.

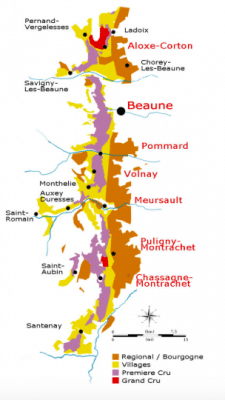

Côte de Beaune

The Côte de Beaune is the Southern half of the Côte d’Or, centred around the town of Beaune. Compared with the Côte de Nuits, the Côte de Beaune is much more focused on white wines, though the majority is still red. It is slightly wider than the Côte de Nuits and while most of the vineyards in the Côte de Nuits face South East, the orientation of vines in the Côte de Beaune is more varied, which may be why the region is both a red and white region.

The main villages, from north to south, are Aloxe-Corton, Beaune, Pommard, Volnay, Meursault, Puligny-Montrachet, and Chassagne-Montrachet. As was the case in the Côte de Nuits, villages have appended the name of their most famous Grand Cru to their name. Another fun fact: the Grand Cru vineyard of Montrachet straddles the villages of Puligny and Chassagne, which is why they have both appended the name.

Reds from the Côte de Beaune can be very good, but they can be a little rustic and lack finesse, and prices are about 40% less expensive than their counterparts from the Côte de Nuits. Whites here can also be very good, verging on sublime (and also very expensive). Grand Cru Montrachet is usually more than $600 per bottle, while village wines from Chassagne or Puligny are usually $60 to $100.

Searching for value is the Côte de Beaune is also possible. Look for red wines from Maranges, Santenay and Ladoix, while whites from Saint Romain, Saint-Aubin and Auxey-Duresses are a bit easier on the pocketbook.

Chablis

Chablis is the northernmost wine district of Burgundy, centred around the town of the same name. The cool climate produces wines with more acidity and flavours less fruity than Chardonnay grown in other parts of the region. These wines often have a flinty note, sometimes described as tasting of gunflint.

Wines can be labelled Petit Chablis, Chablis, Premier Cru Chablis or Grand Cru (there is 1 Grand Cru but 7 climats or vineyards within this Grand Cru).

A special limestone soil with fossilized sea creatures, called Kimmeridgian, is the main feature of Chablis, which may help to explain why it goes well with oysters.

All Grand Cru and Premier Cru vineyards are located on Kimmeridgian Soil, with Chablis and especially Petit Chablis grown on Portlandian soil, a limestone soil that is younger with a higher clay and calcium content.

Grand Cru Chablis is the only Grand Crus from Burgundy that you will find for under $100 – usually in the range of $60 to $90. Premier Crus are usually priced between $40 and $60, Chablis between $25 and $35 and Petit Chablis for $20 to $25.

Côte Chalonnaise

In many ways, the Côte Chalonnaise is a continuation of the Côte d’Or, but with no Grand Cru vineyards. The villages of Bouzeron, Rully, Mercurey, Givry and Montagne can offer very good value wines, and Premier Crus from these villages are usually less than the price of a basic Villages wine from the Côte d’Or.

They are less complex than wines from the Côte d’Or but do not require much aging. A Villages-level Cote Challonaise will cost between $20 and $30, while Premier Cruse can be had for $30 to $40. They are exceedingly good value.

Much of the wines coming from the Côte Chalonnaise are usually declassified to basic regional Bourgogne because it’s usually better known than the village names of this region. It is also the source of much of the grapes used to make Crémant de Bourgogne, the traditional method sparkling wine of the region.

Maconnais

This region takes its name from the town of Mâcon. It is best known as a source of good value white wines made from the Chardonnay grape. Almost all the wine made in the Mâconnais is white wine.

There are no Grand Crus or even Premier Crus in the region, although the wines from Pouilly Fuissé are not only much sought after, they can also rival some of the white wines grown in the Cote d’Or. Other wines of note are Saint Veran, and many wines with Macon in the name (Macon- Chaintré, Macon-Uchizy, Macon-Vinzelles are some of the best).

Most Maconnais wines are priced between $15 and $25, but a good Pouilly Fuissé can run up to $40.

Beaujolais

Depending on who you ask, Beaujolais is or is not part of Burgundy. It concentrates almost exclusively on Gamay, the grape that was outlawed in the 14th Century. Much as the rest of Burgundy looks down on Beaujolais, though, administratively it is part of the region. The official Burgundy Wine website does not even mention Beaujolais. In fact, some of the wines grown here can qualify to be sold as regional level Bourgogne.

The region is best known for the (in)famous Beaujolais Nouveau, which is released to much fanfare on the third Thursday of November. This is barely-fermented grape juice, which is not a wine to be taken seriously. However, as a celebration of the harvest, it has its place. More serious versions of Gamay are made and labelled Beaujolais or Beaujolais Superior.

But without a doubt, the best wines from the region are the 10 Beaujolais crus, which are grown on a large outcrop of granite in the northern part of the area. The crus are named after villages or important landmarks: Brouilly, Régnié, Chiroubles, Côte de Brouilly, Fleurie, Saint-Amour, Chénas, Juliénas, Morgon and Moulin-à-Vent.

Beaujolais Nouveau usually costs about $10, while Beaujolais and Beaujolais Superieur will cost between $12 and $15. Cru Beaujolais is a bit more expensive, usually costing between $15 and $30. However, it is worth trying if you can find it.

The Main Grapes of Burgundy

Pinot Noir

Pinot Noir is the red king of Burgundy. It is thin-skinned, giving it a lighter colour and lower tannins, and fairly high acid. It is widely considered to produce some of the finest wines in the world, but it is a difficult variety to cultivate, a situation which causes some to refer to it as the “heartbreak grape”.

When young, wines tend to have red fruit aromas of cherries, raspberries and strawberries. As the wines age, they have the potential to develop vegetal and “barnyard” aromas that can contribute to the complexity of the wine.

Pinot Noir is widely grown in the Côte d’Or and Côte Chalonnaise.

Chardonnay

If Pinot Noir is the king, then Chardonnay is certainly the Queen of Burgundy. The grape itself is very neutral, with many of the flavours commonly associated with the grape being derived from such influences as terroir and oak.

It is vinified in many different styles, from the lean, crisply mineral wines of Chablis to the oaky and tropical fruit flavours of Montrachet, flavours which have been widely imitated but never replicated in the rest of the world.

Chardonnay is the sole grape variety authorized in Chablis and it reaches its apogee in the Côte de Beaune. Côte Chalonnaise and Macon also widely grow Chardonnay, the latter almost exclusively.

Other Grapes

Other grapes account for less than 10% of Burgundy production, with Aligoté the specialty of Bouzeron, Gamay in Beaujolais and Sauvignon Blanc in a small region called Saint-Bris. These grapes can be grown elsewhere, but they are very minor players, along with small amounts of Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc being used.