Regional Profile

Cru Bourgeois Wine Classification

This article will look at the classification of Cru Bourgeois, its history, advantages and disadvantages as well as some examples of excellent Cru Bourgeois that you should keep an eye out for.

History of Bordeaux Classifications

In 1855, in anticipation of the Paris Expo, Emperor Napoleon III proposed a system for classifying the best Bordeaux wines, so consumers could better understand their quality. Brokers from the wine industry ranked the wines of 58 châteaux from First to Fifth growth according to the reputation and trading price of the wine. This ranked predominantly Médoc châteaux (those on the left bank of the Gironde river). And with the exception of one addition and one promotion, it is barely unchanged almost two hundred years later.

More recently Graves and Saint Emilion have attempted their own classifications but these have been problematic (the Graves attempt because it has only one level and is not subject to revision; the Saint Emilion attempts because they have been abandoned by some of the top wineries). One that has withstood the test of time is the classification of so-called “petit châteaux” in the Médoc, called Cru Bourgeois.

What is Cru Bourgeois?

Cru Bourgeois is a classification of petit châteaux in the Médoc region of Bordeaux. Comprised solely of red wines that offer excellent value for money, it stands in contrast to the classified growths of the 1855 classification. For one, it’s use started quite a bit earlier, having been employed since the middle ages. In the 15th Century, Bordeaux was under British rule and merchants were exempt from taxes on the sale of wine, both domestic and exported, allowing them to make their fortune. This commercial class (bourgeois) was able to buy the best lands in the Médoc and the term “Cru Bourgeois” came into common use.

In 1858, the first listing of Cru Bourgeois was published, with 248 châteaux being divided into three categories. Coming so soon after Napoleon III’s 1855 classification, though, it was largely ignored. However, in 1932, at a time when the French government was codifying laws for various appellations around France, the Bordeaux Chamber of Commerce developed a list of 444 “Cru Bourgeois du Médoc”. Although this was never officially adopted by the French government, it served as a reference point for Médoc estates outside the 1855 classification.

Finally, in 1962, the Union des Cru Bourgeois de Médoc was formed and regulations governing the use of this historic term were officially adopted and recognized by the French and EU governments.

The first classification by the Union des Cru Bourgeois de Médoc was approved in 2003, with 247 of almost 500 candidates accepted into one of three levels: Cru Bourgeois, Cru Bourgeois Supérieurs or Cru Bourgeois Exceptionnels. Almost immediately it was discarded for being unfair since some of the experts determining the classification were themselves owners of châteaux being classified, clearly a conflict of interest.

In response, the Union drew up new rules to include a stringent and blinded quality assurance procedure to save the veracity of the designation and develop a classification that provided consumers with a real guide to quality.

The Current Classification

As of the 2020 classification, there were 249 Cru Bourgeois: 179 in the basic category, 56 classified as Cru Bourgeois Supérieurs and 14 achieving the designation of Cru Bourgeois Exceptionnels.

There are three elements to obtain a five-year Cru Bourgeois designation:

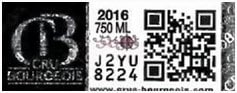

- Blind tasting by a panel of experts to achieve at least Level 3 in the sensory analysis

- Demonstrate a commitment to environmental sustainability by obtaining at least High Environmental Value (HVE) certification

- Guarantee traceability and authenticity through a QR code on the label

Once a châteaux has been classified, it undergoes regular random tasting checks over the five year period. The classification is renewed from scratch every five years.

Elevation to the higher level distinctions of Cru Bourgeois Supérieurs or Cru Bourgeois Exceptionnels require several additional requirements. First, they must specifically apply for the higher level designation they wish to be in. Second, they must gain an associated higher score on the blind tasting. And third, they must demonstrate the implementation of various quality steps in the vineyard and winery, as well as for promotion of their châteaux and wines. Those achieving Cru Bourgeois Exceptionnels must also achieve a 2/3 majority vote by secret ballot of the 6-person Union jury.

This criterion of applying for a specific level is interesting because it requires a certain gamble by those who believe they are at a higher level. For example, if one applies for Supérieurs or Exceptionnels and does not achieve that specific level, they are unable to qualify for a lower level. This means that one must be pretty confident in order to apply for one of these levels. Especially since the tasting is completely blind, and not achieving a tasting level of at least 2 (for Supérieurs) or 1 (for Exceptionnels) means the château receives no classification at all.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Classification

As indicated above, the original 1855 classification as well as those of Graves and Saint Emilion have some serious disadvantages. The Cru Bourgeois classification tries to address the most egregious of these. First, it is dynamic. Every five years châteaux must reapply for one of the three levels, and classification is made without reference to the previous one. Second, it focusses on wine quality. The marks from the blind tasting make up the majority of points toward gaining the classification, which contrasts with, for example, the Saint Emilion classification which places more emphasis on elements like reputation in the marketplace, which bizarrely is more important than wine quality the further up the classification one goes. Finally, there is an element of consistency, since random tasting inspections are undertaken during the five year classification period.

Regulatory bodies have been trying to come up with ways of guaranteeing quality for decades. France’s Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) system was set up in the 1930’s to try to establish a foundation for quality. While they attempt to control viticultural and winemaking practices, such as limiting yield (lower is usually better), abolishing or controlling winemaking adjustments such as acid and sugar, codification of practices does not necessarily guarantee quality to the end consumer. Classification systems try to do this, but they usually represent a snapshot in time, rather than a true guarantee of quality in future. Furthermore, “quality” is very much subjective. Despite the attempt at objectivity by, for example, the Cru Bourgeois evaluation placing significant emphasis on blind tasting. The tasting panel is a group of people who are highly experienced with Médoc red wine as it has been produced in the past, leaving little room for experimentation or alternative styles. Nevertheless, if the goal is to ensure that people who have expectations of what a Cru Bourgeois should taste like are satisfied by their selection, then the Cru Bourgeois classification is at least a step in the right direction.

Another criticism of the system is one that also bedevils the Saint Emilion classification: not all châteaux have agreed to participate. In Saint Emilion, Ausone, Cheval Blanc and Angelus have pulled out of the ranking. Similarly, there are many notable names who have refused to participate in the Cru Bourgeois ranking, including Chasse Spleen, Ormes de Pez and Sociando-Mallet. Like their counterparts in Saint Emilion, these châteaux believe their reputation exceeds that of the classification. That may be true, though it may also be that they are worried the performance of their wines may not match their historic reputations, remember blind tasting makes up most of the weight of the score. Without question, the Exceptionnels level is made poorer by the absence of some of these excellent petit châteaux.

Finding the best Cru Bourgeois

Because of the requirements of the classification, especially the emphasis on blind tasting, consumers can feel a certain amount of confidence when buying Cru Bourgeois. The classification level appears on the front label of a qualified wine, and the traceability QR on the back label (see example).

Consumers can be assured that the wine will deliver what is expected and at a price that is quite reasonable, especially compared with the wines offered by the classified growths. Good Cru Bourgeois can be had for $25.

Consumers can be assured that the wine will deliver what is expected and at a price that is quite reasonable, especially compared with the wines offered by the classified growths. Good Cru Bourgeois can be had for $25.

For those looking for a step up in quality, Cru Bourgeois Supérieurs and Exceptionnels certainly offer that. Remember they must apply for and achieve the level they receive, which means they need to be confident of achieving their result. Consequently, they not only offer a substantial step up from basic Cru Bourgeois, but they often over deliver at their level. Cru Bourgeois Supérieurs generally run up to $50, while Exceptionnels can usually be had for under $60. At this price they are still considerably less than wines from classified growths and can occasionally offer noticeably better quality.

Following is a list of the 14 Cru Bourgeois Exceptionnels:

|

HAUT-MÉDOC |

LISTRAC-MÉDOC |

|

Château Lestage |

|

|

Château Arnauld |

MARGAUX |

|

Château Belle-Vue |

Château d’Arsac |

|

Château Cambon La Pelouse |

Château Paveil de Luze |

|

Château Charmail |

SAINT-ESTÈPHE |

|

Château Malescasse |

Château Le Boscq |

|

Château de Malleret |

Château Le Crock |

|

Château de Taillan |

Château Lilian Ladouys |